By Howell Raines

Chapter Three

(Excerpt)

Sometimes we need to be close to the earth and feel its true age and contemplate its real history. We need to contemplate, as well, the history of man’s imaginings about the earth.

The earth, for example is 4.5 billion years old. Lakes were created, and as the granite resolved itself into soil, trees grew. At some point in all of this, the Maymaygwayshi moved into the sheer rock cliffs that rise straight up a hundred feet from the waters of some Canadian Shield lakes.

They were about three feet tall, mischievous fellows who emerged at night to cut fish from the nets of the Ojibwa. The knowledge that they actually lived inside cliffs came from the reports of Ojibwa shamans who claimed the power to speak to the Maymaygwayshi and trade tobacco for rock medicine.

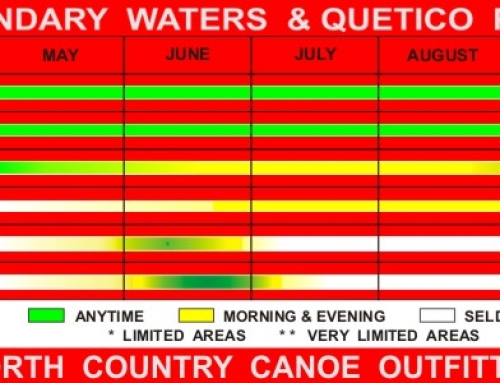

This is how I came to be among the Maymaygwayshi. I had been calling outfitters in Ely, Minnesota because I wanted to fish the lakes in the Boundary Waters and Quetico Park. Outfitters kept saying, “Just come on up. The fishing is great everywhere.”

After four decades of fishing, you learn to recognize this as the most fundamental of all statements of ignorance. The fishing is never great everywhere. Finally I reached a fellow named John Schiefelbein, who owns North Country Canoe Outfitters. He said, “Tell me exactly what kind of fishing you want to do.”

“That’s easy,” I said. “I want to catch very large smallmouth bass on a fly rod.”

“Do you mind working a little to get to your fishing?” John asked. I said I did not. “Then I will send you to the best place in the world,” he said. And maybe he did.

From the time the float plane dropped us at the ranger station on Lac La Croix, we were on our own. It was a foggy day when we set out, the air heavy with water that sometimes congealed into a slow rain. We trolled deep-running lures as we paddled for several hours to get off the big lake and into the network of streams branching from the Maligne River.

“Maligne” means “evil,” and for me the river turned out to be aptly named. Fish were at the lures constantly. I had stopped paddling to remove a small northern pike when it drove one point of a treble hook deep into my thumb. I managed to get the fish off, and then tested to see how soundly I was hooked. In forty years of fishing I had never hooked myself. Now it came in the most remote place I had ever been.

“Jeff,” I said, “you’re going to have to try to get this hook out.”

“How?” he asked.

“That’s what we have to figure out.” Before leaving home, I had ordered a hook removal kit for $4.95 from a fishing catalog. It worked, and with very little pain at that. As Jeff dribbled merthiolate over the unimpressive hole in my thumb, I allowed as how the hook removal kit was under-priced by about $195.05.

I was not in top condition for the hard traveling we were doing as we pressed towards the inner wilderness, and without a word, Jeffrey took the hardest job, that of carrying the canoe, at every portage. We camped for the second night on a grassy point graced by an elegant pine tree. Beside this point ran a torrent of water of fast water called the Darky River, which had its source miles away in a lake by the same name. While unloading the canoe, I casually flipped a popping bug into the torrent and caught a two-pound bass.

The fish I had caught was a creature that possessed an IQ of, say, six; but it taught me a lot. This fish and others that followed it were punctuating moments in a skein of days that Jeff and I shared in a spirit of profound companionability.

It was with this fish that I began to relax. It was a state that was not permanent, not for a long time. But for an instant, I glimpsed the way I had to go. This fish I had hooked by moving slowly, almost indifferently, by casting fewer times, not more, by letting the bass come if it was going to come, to bite if it was going to bite.

I had entered a new knowledge or allowed it to enter me, a circumstance that requires an act of relaxation, a surrender, a submission to the knowledge one wishes to possess.

That night I handed my son Jeff a copy of Huckleberry Finn that I had slipped into my pack. It was not long before Sam Clemmens had worked a mighty spell on him. In our tent, on that evening and on many to follow, his flashlight shone far into the night.

I allowed myself a moment of congratulations for giving Jeff the chance to discover this book in a place where it was still possible to glimpse the untamed continent that young Sam Clemmens knew. In all this — our nation’s greatest yarn, the Indian drawings on the rocks, the moose among the lily pads, the brown fish falling from our fingers into the darkness of their waters — I felt Jeffrey might encounter memories to carry at the center of his heart for years, for a lifetime, perhaps. I know I did.

Many adventures lay before us. We were in a landscape that changed me and changes me still every time I return. Before us lay the water paths and the very campsites packed hard by moose hunting Indians, and by the voyageurs led by the old French fur men. And at the center lay the clifty home of the Maymaygwayshi.