BOUNDARY WATERS BASS: by Howell Raines

In northwestern Ontario, not far from where the Tuck River empties into Crooked Lake, there is a large shallow bay of 1,000 acres or so which straddles the US-Canada border. From the Canadian ranger station on Lac La Croix, it is possible to reach this part of Crooked Lake in four or five days by canoe, with time out for fishing. If you start from Ely, Minnesota, two days of industrious paddling should get you on the US-side of the bay.

My 17-year-old son, Jeffery, and I arrived at this remote place on the ninth evening of an 11-day trip through Quetico Provincial Park. We knew this would be our last evening of serious fly-fishing.

Come morning, we faced a run of hard paddling and portaging to meet our outfitter at Mudro Lake on the Minnesota side of the border. So after we made camp on a piney plateau overlooking this inviting expanse of water, I spoke learnedly to Jeffery of our prospects. This spot, I said to him, offered the vast, reedy shallows where we might take a truly large northern pike, a fish to double the eight-pounder he’d taken on the second day. I showed him an imposing Dahlberg Diver tied on a #2 hook, a big yellow number I had held in reserve during all the days when the smallmouth bass insisted on smaller flies.

Perhaps he did not know, I added, that the legendary Bob Dahlberg had originally tied the diver for northerns. So I concluded, let us abandon the rocky areas where we had taken so many bass and go into the grassy lair of a grim and grand-fatherly pike. It was quite an impressive discourse for a newcomer to North Woods fishing, and Jeff thanked me by paddling the canoe while I cast my Diver among the reeds.

A half hour before dark I had a strike as abrupt as a gunshot and just as violent. I missed it. A little shaken, I continued to cast. A few minutes later, there was another explosion. Again, no hook up.

I spoke of Dahlberg’s genius in creating a fly so irresistible to this inland barracuda. Voracious feeders, I alibied, but highly inaccurate on the strike. Jeff suggested that there ought to be a statute of limitations on our rule that the person in front of the canoe stayed there until he landed a fish.

For 15 gloomy minutes we pressed on across black water stippled every yard or so by a green stalk. No wind. No sign, now, of feeding fish. Then it happened again, an operatic strike that seemed to open a bucket-sized hole in the water. This time I was hooked to something strong, which made a run down a hallway of clear water and jumped to the surface.

Dad, it’s a huge smallmouth! said Jeffery, charitably omitting any commentary on its non- “northern pike” -ness. I had just gotten the fish on the reel when it bulled back into the cover and wrapped the leader around a single tough reed. Jeff paddled over and pulled the stalk loose from the bottom; the fish went into the open water to finish its fight. It weighed four and three-quarters pounds on the had scale, the largest bass of the trip by a few ounces and barely shy of the five-pound mark I had aimed for.

Back in Ely, I was prepared to astonish our outfitted, John Schiefelbein, with news of the catch: He hadn’t marked this bay on the fishing charts he’d prepared for our trip.

Guess where I got my biggest fish? I asked. Without hesitation, he called it within a quarter mile. Now you’ve got my last secret, Schiefelbein said. I had stumbled on to a place where Jerry McKinnis (ESPN) and other television fishermen go for their big-fish footage. You can’t send every party to the same spots, he added, half apologetically. Even here, that kind of pressure will take its toll.

There was no apology necessary. Of all the outfitters I contacted in Ely, Schiefelbein had been the most eager to custom-tailor our trek, rather than simply rent me a tent and a canoe. He pressed me for my top priority and when I said it was to catch a lot of truly large smallmouth bass on a fly rod, he promised to send us to “the best place in the world.”

We flew directly from Schiefelbein’s docks on White Iron Lake near Ely, to Canadian Customs and then on to the Hilly Island ranger station. From there we pressed in to the heart of the Quetico Provincial Park, which is the Canadian sector of the jointly administered wilderness area of 2.75 million acres (yes, you read that right) on the Minnesota-Ontario border. The American side lies on the Superior National Forest, and is called the Boundary Waters Canoe Area.

Since late 1979, outboard motors have been barred from the vast majority of both Quetico and the BWCA. Float planes can only land at the edges of both parks. No planes, no fast boats, no ice machines: It all adds up to catch-and-release fishing in the waters of a vast geological formation call the Canadian Shield.. This is ancient carapace of stone that covers two million square miles of the Lake Superior region.

The pertinent dates for the fly rodder are these: Three billion years ago, the Canadian Shield was formed. Ten thousand years ago, glaciers passed through and gouged out 1,900 lakes within the park area. Then, in 1901, the Ontario Provincial Government decided that the native game fish — northerns, walleyes, and lake trout — needed company, and so introduced smallmouth bass from the central United States. This irritated North Woods purists, but it also produced a fishery where is possible to catch two – to four – pound bass as rapidly as one can catch spawning bluegills in farm pounds of my native Alabama.

Can you catch fish with hawser-like leaders and sloppy presentations? Maybe, but a little expertise doesn’t hurt. Indeed, one of the joys of the BWCA is that fly fishermen of average skill can look like a star, for the sport is in its infancy in these parts.

Ask about famous sly fishermen who have visited the area and you will not hear the names of Lefty or Lee or Gary. Instead, the locals talk about Bobby Knight.

Yes, the basketball coach. Seems he owns a fly rod. I could see that from the video that John Schiefelbein showed me in his office at North Country Canoe Outfitters. It revealed that Knight’s casting, like his coaching, runs more to passion than to finesse. When it came to working his bug, he kept his rod tip pointed at the sky and violated every rule. Even so, the coach and his guide, the aforementioned Jerry McKinnis, host of ESPN-TV’s fishing show THE FISHING HOLE, caught and released sinfully large bass.

I also saw a video of Roland Martin, the famous bass predator, using equally bad form on Crooked Lake. Martin fly-fishes in the old down-home style, stripping line onto the floor of the boat and never doing the fish the honor of putting it on the reel. But he imparted the valuable intelligence that these Canadian-Shield smallmouth sometimes prefer tiny popping bugs.

This came in handy on our second day. Jeff and I had Minn Lake, roughly the size of New Hampshire’s Lake Sunapee, to ourselves. He had worked a big popper for a couple of hours without much success. Finally, remembering Roland. Martin, I tied a frog colored bluegill bug dressed a #8 hook and threw it into open water in the middle of a small cove.

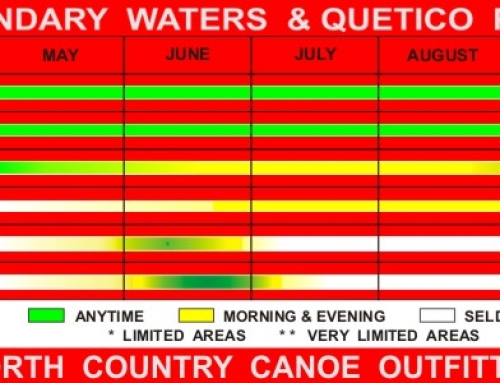

Presently, a fish came up behind the bug, showing its dorsal fin and then sinking from sight in the manner of a saltwater fish inspecting a trolled lure. I moved the bug six inches, very gently, and the fish, a three-pounder, took it with a refined slurp. That technique — small bugs fished from shore — proved very effective on these late-summer fish. The reason for this, I think, is that in July and August the fish like to hold in 10 to 15 feet of water, and evenings find then rising in place rather that holding against the shoreline.

This year I plan to return for the June spawn, and I expect to find the bass taking aggressively along the bouldery shorelines where, according the book, they’re supposed to live. The lack of extensive literature on fly-fishing for Ontario smallmouth is kind of appealing; this fishing provided an opportunity to fall back on common sense rather than the index of a how-to-book.

So, here’s your common sense guide:

FLIES: In wet flies, the idea is to imitate leeches, crayfish, and frogs. I favor Woolly Buggers and Clouser’s Deep Minnows. Take deer hair and cork poppers in white, yellow, brown, and green, and of course Dahlberg Diver for your northern pike demonstration.

RODS: Wind was not a problem, so we hardly used our 7 – and 8 – weight rods. I found the 9-foot rod that Dave McNeese built for me on a first generation Sage blank ideal, but then I find this rod ideal for almost everything, especially since I strengthened the butt with an internal splint. This year, I’m taking a #3 outfit also built by McNeese, on a sage representative blank, just for the entertainment value.

Television fishing shows and articles about Ontario smallmouth are likely to speak of the “the Crooked Lake area” or “the Lac La Croix area.” You should think of Crooked Lake and Lac La Croix as highways. They served as just that for the Ojibwa Indians, for the French voyageurs who opened this country to the fur trade in the 18th Century, and for loggers who came after. You should also be aware that referring to these “areas” is a dodge; it allows those in the know to omit the names of specific lakes that provide the best fishing. Here we must confront a painful fact of this, our favored sporting life: People will suffer memory lapses, or just plain lie, when it comes to their absolute favorite spots.

Common sense can provide some sort of protection from this sort of mendacity. Simply remember the farther you move out into the BWCA bush, the better the fishing gets. Also remember that smallmouth bass love moving water. These lakes are connected by rivers and creeks, and the big pools in these streams offer excellent fishing that is often over looked. And wherever you find a stream dumping a heavy current into a lake, you are almost certain to find congregations of bass.

Beyond that, interrogate your outfitter. The better ones make annual trips to check on their favorite lakes. John Schiefelbein keeps a regularly updated computerized list of the best spots on specific lakes. Perhaps you can twist out of him the location of the bay where I delivered my pike lecture. You’d be in business right away — if I’d told him the truth. Right now, I can’t remember…

I can’t swear that John Schiefelbein told the truth when he said that the BWCA is the best place in the world to fly-fish for smallmouth bass. But I’d bet my house it’s got to be in anyone’s top five.

Reprinted by permission.